Book XI¶

Elementary Stereometry¶

Theory of planes, coplanar lines, and solid angles

Definitions¶

XI.def.1

A solid is that which has length, breadth, and depth.

XI.def.2

An extremity of a solid is a surface.

XI.def.3

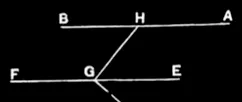

A straight line is at right angles to a plane, when it makes right angles with all the straight lines which meet it and are in the plane.

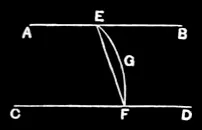

XI.def.4

A plane is at right angles to a plane when the straight lines drawn, in one of the planes, at right angles to the common section of the planes are at right angles to the remaining plane.

XI.def.5

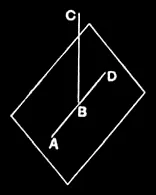

The inclination of a straight line to a plane is, assuming a perpendicular drawn from the extremity of the straight line which is elevated above the plane to the plane, and a straight line joined from the point thus arising to the extremity of the straight line which is in the plane, the angle contained by the straight line so drawn and the straight line standing up.

XI.def.6

The inclination of a plane to a plane is the acute angle contained by the straight lines drawn at right angles to the common section at the same point, one in each of the planes.

XI.def.7

A plane is said to be similarly inclined to a plane as another is to another when the said angles of the inclinations are equal to one another.

XI.def.8

Parallel planes are those which do not meet.

XI.def.9

Similar solid figures are those contained by similar planes equal in multitude.

XI.def.10

Equal and similar solid figures are those contained by similar planes equal in multitude and in magnitude.

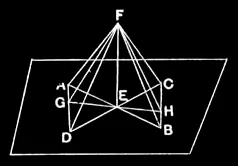

XI.def.11

A solid angle is the inclination constituted by more than two lines which meet one another and are not in the same surface, towards all the lines.

XI.def.12

A pyramid is a solid figure, contained by planes, which is constructed from one plane to one point.

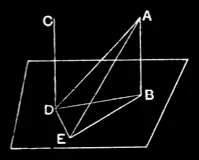

XI.def.13

A prism is a solid figure contained by planes two of which, namely those which are opposite, are equal, similar and parallel, while the rest are parallelograms.

XI.def.14

When, the diameter of a semicircle remaining fixed, the semicircle is carried round and restored again to the same position from which it began to be moved, the figure so comprehended is a sphere.

XI.def.15

The axis of the sphere is the straight line which remains fixed and about which the semicircle is turned.

XI.def.16

The centre of the sphere is the same as that of the semicircle.

XI.def.17

A diameter of the sphere is any straight line drawn through the centre and terminated in both directions by the surface of the sphere.

XI.def.18

When, one side of those about the right angle in a right-angled triangle remaining fixed, the triangle is carried round and restored again to the same position from which it began to be moved, the figure so comprehended is a cone.

XI.def.19

The axis of the cone is the straight line which remains fixed and about which the triangle is turned.

XI.def.20

And the base is the circle described by the straight line which is carried round.

XI.def.21

When, one side of those about the right angle in a rectangular parallelogram remaining fixed, the parallelogram is carried round and restored again to the same position from which it began to be moved, the figure so comprehended is a cylinder.

XI.def.22

The axis of the cylinder is the straight line which remains fixed and about which the parallelogram is turned.

XI.def.23

And the bases are the circles described by the two sides opposite to one another which are carried round.

XI.def.24

Similar cones and cylinders are those in which the axes and the diameters of the bases are proportional.

XI.def.25

A cube is a solid figure contained by six equal squares.

XI.def.26

An octahedron is a solid figure contained by eight equal and equilateral triangles.

XI.def.27

An icosahedron is a solid figure contained by twenty equal and equilateral triangles.

XI.def.28

A dodecahedron is a solid figure contained by twelve equal, equilateral, and equiangular pentagons.

Propositions¶

XI.1

A part of a straight line cannot be in the plane of reference and a part in a plane more elevated.

XI.2

If two straight lines cut one another, they are in one plane, and every triangle is in one plane.

XI.3

If two planes cut one another, their common section is a straight line.

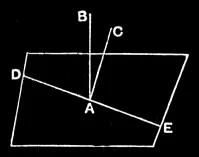

XI.4

If a straight line be set up at right angles to two straight lines which cut one another, at their common point of section, it will also be at right angles to the plane through them.

XI.5

If a straight line be set up at right angles to three straight lines which meet one another, at their common point of section, the three straight lines are in one plane.

XI.6

If two straight lines be at right angles to the same plane, the straight lines will be parallel.

XI.7

If two straight lines be parallel and points be taken at random on each of them, the straight line joining the points is in the same plane with the parallel straight lines.

XI.8

If two straight lines be parallel, and one of them be at right angles to any plane, the remaining one will also be at right angles to the same plane.

XI.9

Straight lines which are parallel to the same straight line and are not in the same plane with it are also parallel to one another.

XI.10

If two straight lines meeting one another be parallel to two straight lines meeting one another not in the same plane, they will contain equal angles.

XI.11

From a given elevated point to draw a straight line perpendicular to a given plane.

XI.12

To set up a straight line at right angles to a given plane from a given point in it.

XI.13

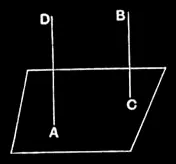

From the same point two straight lines cannot be set up at right angles to the same plane on the same side.

XI.14

Planes to which the same straight line is at right angles will be parallel.

XI.15

If two straight lines meeting one another be parallel to two straight lines meeting one another, not being in the same plane, the planes through them are parallel.

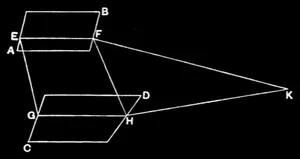

XI.16

If two parallel planes be cut by any plane, their common sections are parallel.

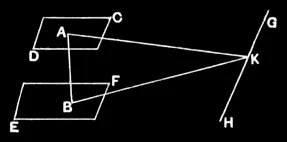

XI.17

If two straight lines be cut by parallel planes, they will be cut in the same ratios.

XI.18

If a straight line be at right angles to any plane, all the planes through it will also be at right angles to the same plane.

XI.19

If two planes which cut one another be at right angles to any plane, their common section will also be at right angles to the same plane.

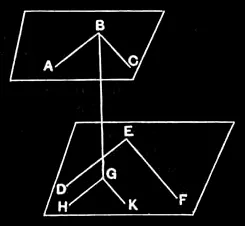

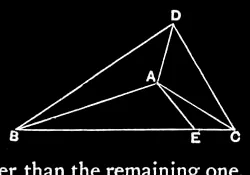

XI.20

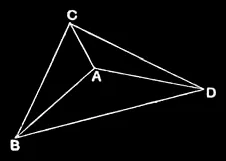

If a solid angle be contained by three plane angles, any two, taken together in any manner, are greater than the remaining one.

XI.21

Any solid angle is contained by plane angles less than four right angles.

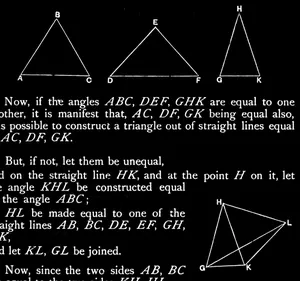

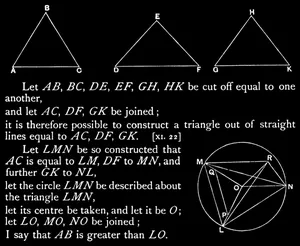

XI.22

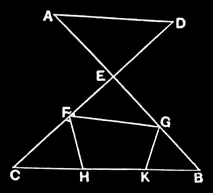

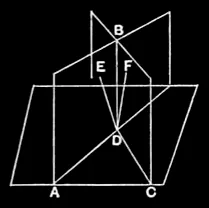

If there be three plane angles of which two, taken together in any manner, are greater than the remaining one, and they are contained by equal straight lines, it is possible to construct a triangle out of the straight lines joining the extremities of the equal straight lines.

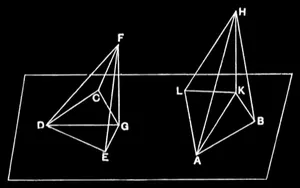

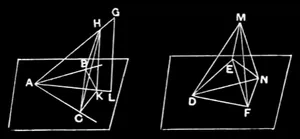

XI.23

To construct a solid angle out of three plane angles two of which, taken together in any manner, are greater than the remaining one: thus the three angles must be less than four right angles.

XI.24

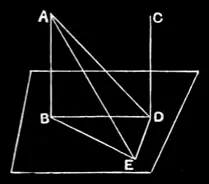

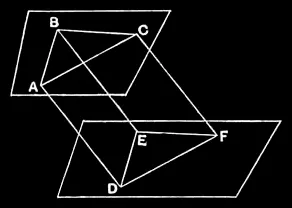

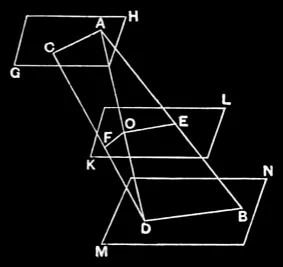

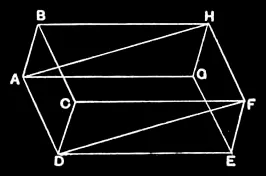

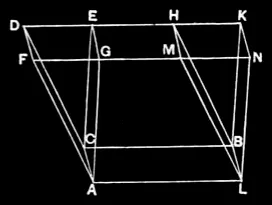

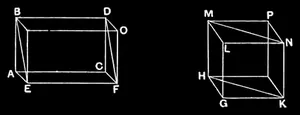

If a solid be contained by parallel planes, the opposite planes in it are equal and parallelogrammic.

XI.25

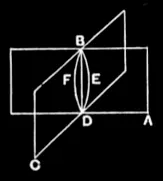

If a parallelepipedal solid be cut by a plane which is parallel to the opposite planes, then, as the base is to the base, so will the solid be to the solid.

XI.26

On a given straight line, and at a given point on it, to construct a solid angle equal to a given solid angle.

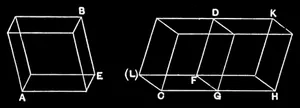

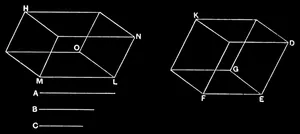

XI.27

On a given straight line to describe a parallelepipedal solid similar and similarly situated to a given parallelepipedal solid.

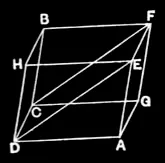

XI.28

If a parallelepipedal solid be cut by a plane through the diagonals of the opposite planes, the solid will be bisected by the plane.

XI.29

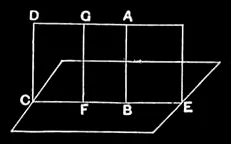

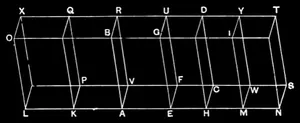

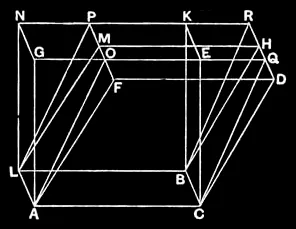

Parallelepipedal solids which are on the same base and of the same height, and in which the extremities of the sides which stand up are on the same straight lines, are equal to one another.

XI.30

Parallelepipedal solids which are on the same base and of the same height, and in which the extremities of the sides which stand up are not on the same straight lines, are equal to one another.

XI.31

Parallelepipedal solids which are on equal bases and of the same height are equal to one another.

XI.32

Parallelepipedal solids which are of the same height are to one another as their bases.

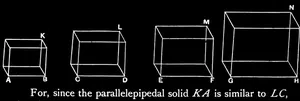

XI.33

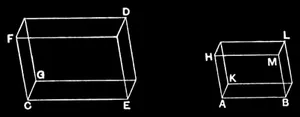

Similar parallelepipedal solids are to one another in the triplicate ratio of their corresponding sides.

XI.34

In equal parallelepipedal solids the bases are reciprocally proportional to the heights; and those parallelepipedal solids in which the bases are reciprocally proportional to the heights are equal.

XI.35

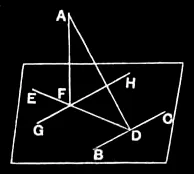

If there be two equal plane angles, and on their vertices there be set up elevated straight lines containing equal angles with the original straight lines respectively, if on the elevated straight lines points be taken at random and perpendiculars be drawn from them to the planes in which the original angles are, and if from the points so arising in the planes straight lines be joined to the vertices of the original angles, they will contain, with the elevated straight lines, equal angles.

XI.36

If three straight lines be proportional, the parallelepipedal solid formed out of the three is equal to the parallelepipedal solid on the mean which is equilateral, but equiangular with the aforesaid solid.

XI.37

If four straight lines be proportional, the parallelepipedal solids on them which are similar and similarly described will also be proportional; and, if the parallelepipedal solids on them which are similar and similarly described be proportional, the straight lines will themselves also be proportional.

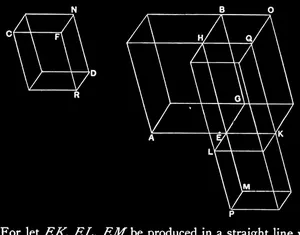

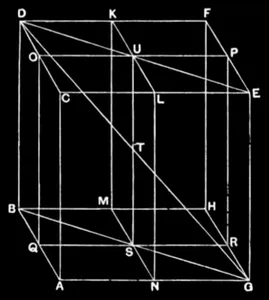

XI.38

If the sides of the opposite planes of a cube be bisected, and planes be carried through the points of section, the common section of the planes and the diameter of the cube bisect one another.

XI.39

If there be two prisms of equal height, and one have a parallelogram as base and the other a triangle, and if the parallelogram be double of the triangle, the prisms will be equal.