Book V¶

Theory of Proportion¶

The theory of proportion set out in this book is generally attributed to Eudoxus of Cnidus. The novel feature of this theory is its ability to deal with irrational magnitudes, which had hitherto been a major stumbling block for Greek mathematicians. Throughout the footnotes in this book, α, β, γ, etc., denote general (possibly irrational) magnitudes, whereas m, n, l, etc., denote positive integers > - Heiberg

Definitions¶

V.def.1

A magnitude is a part of a magnitude, the less of the greater, when it measures the greater.

V.def.2

The greater is a multiple of the less when it is measured by the less.

V.def.3

A ratio is a sort of relation in respect of size between two magnitudes of the same kind.

V.def.4

Magnitudes are said to have a ratio to one another which are capable, when multiplied, of exceeding one another.

V.def.5

Magnitudes are said to be in the same ratio, the first to the second and the third to the fourth, when, if any equimultiples whatever be taken of the first and third, and any equimultiples whatever of the second and fourth, the former equimultiples alike exceed, are alike equal to, or alike fall short of, the latter equimultiples respectively taken in corresponding order.

V.def.6

Let magnitudes which have the same ratio be called proportional.

V.def.7

When, of the equimultiples, the multiple of the first magnitude exceeds the multiple of the second, but the multiple of the third does not exceed the multiple of the fourth, then the first is said to have a greater ratio to the second than the third has to the fourth.

V.def.8

A proportion in three terms is the least possible.

V.def.9

When three magnitudes are proportional, the first is said to have to the third the duplicate ratio of that which it has to the second.

V.def.10

When four magnitudes are <continuously> proportional, the first is said to have to the fourth the triplicate ratio of that which it has to the second, and so on continually, whatever be the proportion.

V.def.11

The term corresponding magnitudes is used of antecedents in relation to antecedents, and of consequents in relation to consequents.

V.def.12

Alternate ratio means taking the antecedent in relation to the antecedent and the consequent in relation to the consequent.

V.def.13

Inverse ratio means taking the consequent as antecedent in relation to the antecedent as consequent.

V.def.14

Composition of a ratio means taking the antecedent together with the consequent as one in relation to the consequent by itself.

V.def.15

Separation of a ratio means taking the excess by which the antecedent exceeds the consequent in relation to the consequent by itself.

V.def.16

Conversion of a ratio means taking the antecedent in relation to the excess by which the antecedent exceeds the consequent.

V.def.17

A ratio ex aequali arises when, there being several magnitudes and another set equal to them in multitude which taken two and two are in the same proportion, as the first is to the last among the first magnitudes, so is the first to the last among the second magnitudes;

V.def.18

A perturbed proportion arises when, there being three magnitudes and another set equal to them in multitude, as antecedent is to consequent among the first magnitudes, so is antecedent to consequent among the second magnitudes, while, as the consequent is to a third among the first magnitudes, so is a third to the antecedent among the second magnitudes.

Propositions¶

V.1

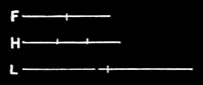

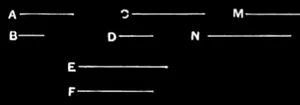

If there be any number of magnitudes whatever which are, respectively, equimultiples of any magnitudes equal in multitude, then, whatever multiple one of the magnitudes is of one, that multiple also will all be of all.

V.2

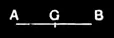

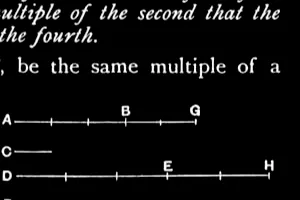

If a first magnitude be the same multiple of a second that a third is of a fourth, and a fifth also be the same multiple of the second that a sixth is of the fourth, the sum of the first and fifth will also be the same multiple of the second that the sum of the third and sixth is of the fourth.

V.3

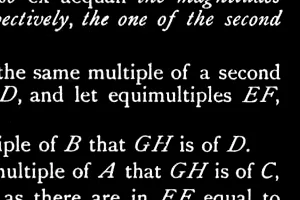

If a first magnitude be the same multiple of a second that a third is of a fourth, and if equimultiples be taken of the first and third, then also ex aequali the magnitudes taken will be equimultiples respectively, the one of the second and the other of the fourth.

V.4

If a first magnitude have to a second the same ratio as a third to a fourth, any equimultiples whatever of the first and third will also have the same ratio to any equimultiples whatever of the second and fourth respectively, taken in corresponding order.

V.5

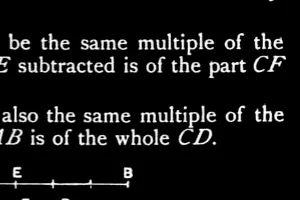

If a magnitude be the same multiple of a magnitude that a part subtracted is of a part subtracted, the remainder will also be the same multiple of the remainder that the whole is of the whole.

V.6

If two magnitudes be equimultiples of two magnitudes, and any magnitudes subtracted from them be equimultiples of the same, the remainders also are either equal to the same or equimultiples of them.

V.7

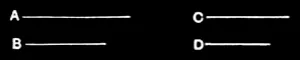

Equal magnitudes have to the same the same ratio, as also has the same to equal magnitudes.

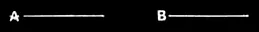

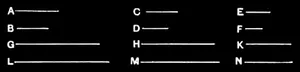

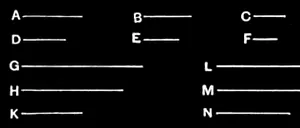

V.8

Of unequal magnitudes, the greater has to the same a greater ratio than the less has; and the same has to the less a greater ratio than it has to the greater.

V.9

Magnitudes which have the same ratio to the same are equal to one another; and magnitudes to which the same has the same ratio are equal.

V.10

Of magnitudes which have a ratio to the same, that which has a greater ratio is greater; and that to which the same has a greater ratio is less.

V.11

Ratios which are the same with the same ratio are also the same with one another.

V.12

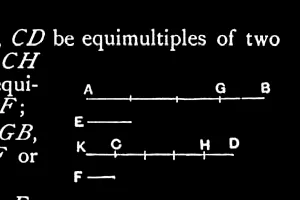

If any number of magnitudes be proportional, as one of the antecedents is to one of the consequents, so will all the antecedents be to all the consequents.

V.13

If a first magnitude have to a second the same ratio as a third to a fourth, and the third have to the fourth a greater ratio than a fifth has to a sixth, the first will also have to the second a greater ratio than the fifth to the sixth.

V.14

If a first magnitude have to a second the same ratio as a third has to a fourth, and the first be greater than the third, the second will also be greater than the fourth; if equal, equal; and if less, less.

V.15

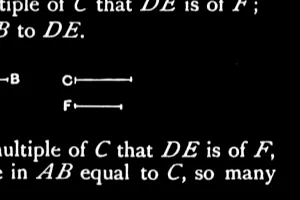

Parts have the same ratio as the same multiples of them taken in corresponding order.

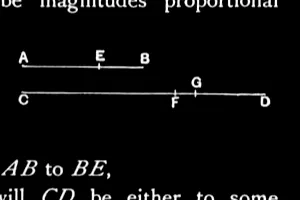

V.16

If four magnitudes be proportional, they will also be proportional alternately.

V.17

- If magnitudes be proportional

componendo, they will also be proportional separando.

V.18

- If magnitudes be proportional

separando, they will also be proportional componendo.

V.19

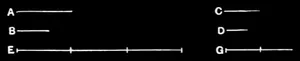

If, as a whole is to a whole, so is a part subtracted to a part subtracted, the remainder will also be to the remainder as whole to whole.

V.20

- If there be three magnitudes, and others equal to them in multitude, which taken two and two are in the same ratio, and if

ex aequali the first be greater than the third, the fourth will also be greater than the sixth; if equal, equal; and, if less, less.

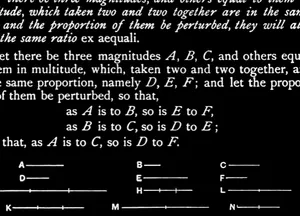

V.21

- If there be three magnitudes, and others equal to them in multitude, which taken two and two together are in the same ratio, and the proportion of them be perturbed, then, if ex aequali

the first magnitude is greater than the third, the fourth will also be greater than the sixth; if equal, equal; and if less, less.

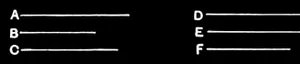

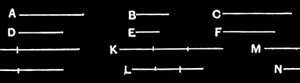

V.22

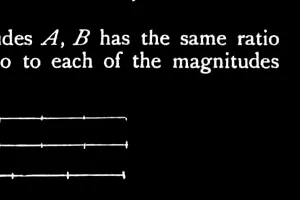

If there be any number of magnitudes whatever, and others equal to them in multitude, which taken two and two together are in the same ratio, they will also be in the same ratio ex aequali.

V.23

- If there be three magnitudes, and others equal to them in multitude, which taken two and two together are in the same ratio, and the proportion of them be perturbed, they will also be in the same ratio

ex aequali.

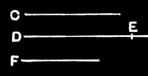

V.24

If a first magnitude have to a second the same ratio as a third has to a fourth, and also a fifth have to the second the same ratio as a sixth to the fourth, the first and fifth added together will have to the second the same ratio as the third and sixth have to the fourth.

V.25

If four magnitudes be proportional, the greatest and the least are greater than the remaining two.