I.20¶

In any triangle two sides taken together in any manner are greater than the remaining one.

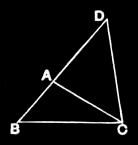

For let ABC be a triangle; I say that in the triangle ABC two sides taken together in any manner are greater than the remaining one, namely BA, AC greater than BC, AB, BC greater than AC, BC, CA greater than AB.

For let BA be drawn through to the point D, let DA be made equal to CA, and let DC be joined.

- Then, since

DAis equal toAC, the angleADCis also equal to the angleACD; [I.5] therefore the angle

BCDis greater than the angleADC. [I.cn.5]

And, since DCB is a triangle having the angle BCD greater than the angle BDC, and the greater angle is subtended by the greater side, [I.19] therefore DB is greater than BC.

But DA is equal to AC; therefore BA, AC are greater than BC.

Similarly we can prove that AB, BC are also greater than CA, and BC, CA than AB.

Therefore etc.

Q. E. D.

Note

It was the habit of the Epicureans, says Proclus (p. 322), to ridicule this theorem as being evident even to an ass and requiring no proof, and their allegation that the theorem was known

(γνώριμον) even to an ass was based on the fact that, if fodder is placed at one angular point and the ass at another, he does not, in order to get to his food, traverse the two sides of the triangle but only the one side separating them (an argument which makes Savile exclaim that its authors were digni ipsi, qui cum Asino foenum essent,

78). Proclus replies truly that a mere perception of the truth of the theorem is a different thing from a scientific proof of it and a knowledge of the reason

whyit is true. Moreover, as Simson says, the number of axioms should not be increased without necessity.